Memory problems

Memory is formed by separate processes and systems that are built up from neural structures.

Memories are not stored in one place in the brain and are not evenly distributed across all brain areas.

It is therefore understandable that if brain damage has occurred in one of these areas, cooperation between these areas becomes difficult.

In order to remember, attention and perception must work at an optimal level. If there is no optimal cooperation, the person in question loses the correct information about what happened.

The more often something is repeated, the more information can be remembered.

That is why people remember something better if photos or memos that are stuck up are looked at regularly.

In order to remember something consciously, it helps if something special happens at the same time or special characteristics stand out.

Remembering new information often takes much longer after sustaining a brain injury than before and information is often not retained well.

This usually has to do with attention problems and mental slowness. In addition, retrieving information from memory can become more difficult.

This usually has to do with attention problems and mental slowness. In addition, retrieving information from memory can become more difficult.

It often happens that someone with a brain injury forgets important information and remembers 'normal' things. This has nothing to do with the so-called 'selective memory'.

Forgetting something is not done on purpose. It has everything to do with whether someone was alert, overloaded or tired at the moment that information HAD to be remembered. If the brain was already busy with other things, it cannot 'write away' information to the working memory or long-term memory at the same time.

The inability to imprint may be related to damage to the hippocampus or other brain areas involved in memory.

(See our special page on memory).

Why do I sometimes forget what is important and remember what is not important?

Specific memory problems also occur after brain damage.

For example, people who have suffered brain damage no longer recognize certain objects (agnosia) or cannot remember certain faces (prosopagnosia).

It has now become known that practicing with all kinds of memory games hardly changes anything in daily life.

Due to the lack of generalization (transferring training effects in the practice situation to daily life), training must always be focused on what one wants to learn.

The problem of forgetting groceries, losing keys, forgetting appointments, etc., cannot therefore be solved by card games and computer training.

Memory training therefore does not have the effect of improving memory. It is not the case that you automatically remember better after memory training.

You learn to remember things better through all kinds of memory tricks (strategy training/compensation training).

Most memory training comes down to the following things: more attention, more time, more repetition, learning to make more connections, learning to think more in images (visual support) and better and more organizing.

- Attention

- Time

- Repetition

- Associating or linking (making connections, making mnemonics, linking funny characteristics to remember a name)

- Visualizing (linking pictures in your memory; forming a picture in your head with a word)

- Organizing

Multiple causes

Difficulty with memory or difficulty remembering faces or objects (recognizing them) is common after brain injury. It can have multiple causes:

- problems storing information

- no longer being able to (properly) retrieve stored information

- lesion in the area where recognition of objects is located:

agnosia - lesion in the area where recognition of faces is located:

prosopagnosia - CVI difficulty recognizing objects, faces and changing sharp vision. This is therefore not a memory problem but can appear that way to bystanders.

- reduced attention and concentration, which means that people are less able to focus on information and for a shorter period of time.

- slowed speed of information processing, which means that information is less well stored in the memory.

- fatigue that plays a role in the reduced ability to store information.

-

filling in 'gaps' in memory with what seems most logical to the person due to problems with short-term memory. It is also called confabulating. This is not done consciously. The person is not lying, but is convinced of the truth. It can lead to a huge battle of words if the environment wants to point out the inaccuracies to the person.

-

déjà vu, the feeling that something has been seen or experienced before. Brain scans show that the frontal areas of the brain monitor our memories and send signals when a memory error occurs.

Normally, the hippocampus takes care of memories. Such a memory error is a conflict between what we have really experienced and what we think we have experienced.

Not in one place in the brain

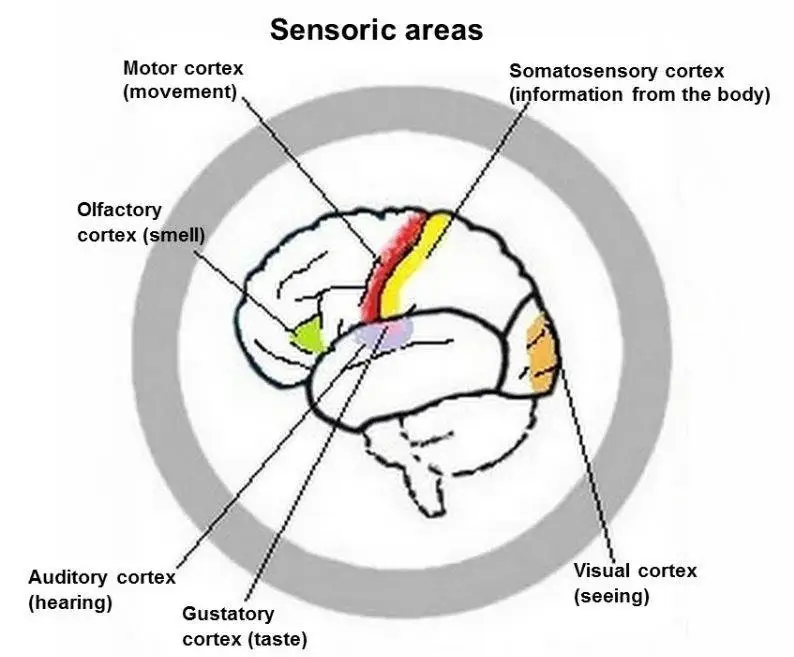

Memory is not in one place in the brain. Many areas are involved in memory:

- The hippocampus

- The temporal lobes

- The lower parts of the cortex of the frontal lobes

- The limbic system, especially the amygdala

- Perirhinal cortex

- Basal ganglia

- Sensoric areas, where all information from the senses is processed

Memory has a special way of storing fearful memories. We have created a special page about that.

Read more about the different memories, such as long-term memory, short-term memory and 'the hole' in memory.

Dealing with short-term memory problems

It is important that you can talk about short-term memory problems as a family or a group of friends, without any rejection and sometimes with humor.

Everyone will want to prevent the person with the short-term memory problem from feeling stupid or rejected.

Correcting quickly gives a feeling of failure. It is important to offer order and structure.

If possible, discuss it and explain that many brain areas are involved in remembering. See our page on memory.

Agree on a hand gesture with people around you, so that if you tell something twice, he or she will alert you that you are telling it twice.

This will save a lot of energy.

For family members and friends: humor but especially understanding are important in all of this. Don't embarrass a person. Don't put her or him on display or correct him or her excessively. A small hint where possible is helpful.

Someone told us: "the worst thing is the fact that you have to trust someone when he/she says that you were told that (a few days ago) and you don't remember it at all. If you then start thinking that someone can make you believe anything because you don't remember it anymore, then you become super suspicious and you shouldn't want that. You should also discuss this".

This shows once again that uncertainty, mistrust and fear of failure can occur as a side effect of a damaged memory.

The environment will have to be very attentive to this, so as not to reinforce it. Prevent psychological damage from becoming one of the invisible consequences of brain injury.

Confabulating

In this section we discuss the phenomenon of confabulation. It is also called memory error or false memory.

It involves telling incorrect, misinterpreted, distorted, exaggerated or fantasized stories due to damage to the brain.

The person then fills in the 'gaps' in the memory, by what seems most logical. Among other things, due to problems with short-term memory or because one has no insight into the disease due to brain damage or due to dementia (anosognosia).

Confabulation can be a consequence of brain injury, schizophrenia, dementia in general, Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and Korsakoff's syndrome.

Korsakoff's syndrome is a neurological disorder caused by a severe vitamin B deficiency (thiamine deficiency), which is usually, but not always, caused by chronic alcoholism.

Neurological and neuropsychological problem

First of all, it is important to realize that confabulation is a direct result of brain damage.

Imprinting, storing, retrieving a memory does not work properly.

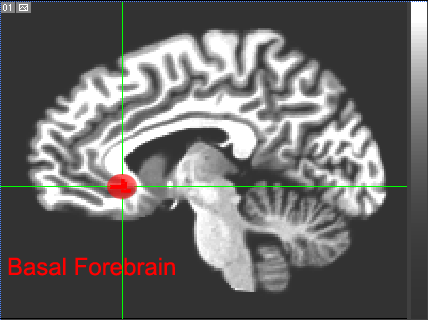

The brain areas that are generally associated with confabulation are:

- the frontal lobes

- the hippocampus or seahorse

- basal forebrain (pars basalis telencephali), see image below

Basal forebrain

The basal forebrain consists of, among other things:

- nucleus accumbens

- nucleus basalis of Meynert

- substantia innominata

- diagonal band of Broca

- nucleus septalis medialis

By Niubrad - Own work, Public Domain wikimedia.org

The person who is confabulating really believes what he or she is telling

Confabulating is something completely different from consciously lying or consciously making something up.

The 'false memories' often sound plausible and are therefore indistinguishable from real memories.

The story can be very probable or very improbable. It happens that a person tells a story completely coherently and plausibly or very incoherently and unrealistically.

A person may remember events that:

- took place at a different time

- took place at a different time

- took place mixed with other events

- took place but were filled in with details that don't add up

- never happened, a new memory can be created of something that never happened.

NB! The sad fact can also occur that a person who confabulates can accuse others of something that never happened.

There is currently no direct treatment that can specifically reduce confabulations.

In only a few cases can confabulation be addressed with psychotherapeutic and cognitive behavioral treatments. The aim is to make people more aware of the inaccuracies in their memory.

How to deal with someone who confabulates

Realize that confabulation also occurs in people without brain damage. Most people have probably created a false memory at some point in their lives. This is how the brain often deals with normal gaps in memory. However, it is not an everyday occurrence in people without brain damage.

A correction or a confrontation can feel like a threat to identity.

Psychologists therefore advise not to confront the person directly with the false memory, let alone in public. The person himself will often not be convinced of the untruth of the memory.

It becomes a lot more difficult if that person becomes angry or aggressive because of her or his own truth, starts making accusations and becomes a danger to her-or himself and others.

If the person is aware of the fact that he or she is confabulating a good conversation, at a different time than the time the confabulation took place, is advisable.

The feeling of being 'caught in the act' can cause enormous shame and doubt about self-worth in addition to emotional problems. Especially if the confrontation takes place in company. Realize that emotional stress can worsen the problem of confabulating.

Ask the person in the conversation if he or she notices that memory sometimes causes problems. Ask how he or she experiences that. Ask if it causes uncertainty. Address that feeling if it is there. Do not deny it. Ask what you can agree on together if you notice that the memory problem is playing up.

Confirm that you recently noticed that something he or she said was not correct. Confirm that you think it is a gap in memory and that it is normal for the brain to fill that in with something that is very probable. Confirm that you know that he or she is not lying or deliberately twisting the facts, but it is a consequence of the brain injury.

Is it your partner who is confabulating? Seek support if he or she finds it difficult that your partner is changing so much.

You may be able to get support from an individual counselor who specializes in brain injury, a practice assistant from your GP or a professional who provides partner and relationship counseling for people with brain injury.

In situations where confabulating is a result of a form of dementia, a dementia case manager may be able to provide advice. Be sure to tell them that you know it is a result of the brain injury. Not every professional is familiar with this problem.

Research into confabulation in Korsakov's disease behind this link.