Small Vessel Disease

What is SVD

Small vessel disease is a disorder of the smallest blood vessels, the capillaries and the arterioles.

This may lead to reduced or interrupted blood flow (perfusion), for example in the brain. SVD can also occur in the kidneys or in the retina of the eye.

SVD falls under cerebrovascular diseases (diseases of the blood vessels in the brain).

It is not an innocent phenomenon. Small Vessel Disease is the cause of approximately 5% of cerebral infarctions (strokes) and is one of the causes of vascular dementia.

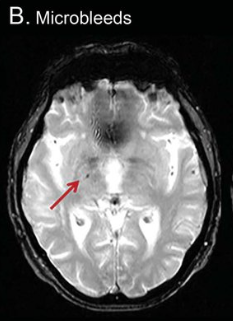

The small blood vessels in the brain may be damaged by microbleeds or by a blood clot getting stuck.

This extremely minor damage to the smallest blood vessels in the brain can lead to damage to surrounding nerves. This means that a local problem in the brain can lead to global brain problems and brain damage.

Risk factors and causes

High bloodpressure (hypertension) is the main risk factor for this cerebral small vessel disease in addition to human aging.

Inadequate supply of blood to the brain (hypoperfusion) due to a narrowing of the common carotid arteries is also a major cause.

This narrowing occurs on both sides of the neck (bilateral stenosis). This can lead to multiple small brain infarcts in the subcortical nuclei (the hypothalamus, the cerebellum, the amygdala and the basal ganglia), resulting in a decrease in brain tissue (atrophy).

Other possible causes mentioned are: obesity, smoking and poor sleep patterns.

Depression is also recognized as a vascular risk factor.

SVD may be a response to inflammation, but it is not known which factor(s) predominate in its pathogenesis. A scientific study linked systemic inflammation in the body in middle age to SVD in later life. These are conditions in which the immune system is disrupted and attacks the body (autoimmune diseases).

Complaints

SVD can manifest itself in vascular cognitive impairment:

- difficulty and decline in thinking

- difficulty remembering, and other memory problems

- delayed information processing

- having difficulty keeping an overview

- having problems with planning and organizing (executive functions)

See more info: cognitive problems

- it can lead to vascular dementia

The severity of these complaints may vary.

SVD can also manifest itself in problems with mobility:

- difficulty moving and walking

- parkinsonism (more info behind the link). For example, complaints of a shaking hand or shaking legs or arms, reduced movement (hypokinesia), slowed movements (bradykinesia), disturbed posture, postural deviation, disturbed postural reflexes, loss of postural reflexes and/or stiff limbs

Because damage to the smallest cerebral vessels can occur anywhere in the brain, very different symptoms can be seen.

This depends on the area of the brain that is affected and the role in the functional network.

If someone has manifestations of small vessel disease in the motor cortex, from which movements are controlled, it is logical that this person, for example, has difficulty walking.

In general, we also hear from people that they have difficulty with stimuli. Sounds come in louder and crowds are no longer tolerated. This can lead to overstimulation and becoming physically ill from ordinary stimuli.

Almost everyone from the age of sixty has SVD to a greater or lesser extent. Not everyone suffers from this.

Possible consequences of SVD

As mentioned above, SVD is one of the causes of vascular dementia.

Vascular dementia is a form of dementia caused by problems in the blood flow to the brain. If the blood flow is not good, oxygen deficiency in the brain can occur.

This can cause brain cells to die and the brain can have problems processing information.

See more information on our special page about vascular dementia.

SVD can lead to a cerebral infarction (stroke) with all possible

consequences, partly depending on which brain area has been affected.

Different course: mild, severe or even progress

The impact of a diagnosis, or of what someone may still have to deal with in the future, can make a person very insecure. It can make them feel unsafe. It is also good to know that SVD can manifest itself differently in everyone and that the course cannot be predicted.

In some cases it is milder than in others. In some cases, progress was seen (see the research by Radboud University in Nijmegen).

It is a good idea to ask for support, for example, from individual guidance if the brain injury causes problems in daily life, or for processing decreased health. For example, through psychological support. In the case of vascular dementia, a dementia case manager is the right person for help and support. Ask your GP for a referral.

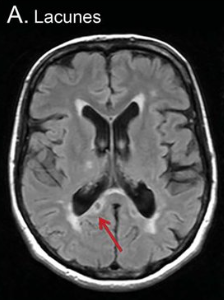

Visualizing SVD with a brain scan

Not everything can be visualized with a brain scan. For example, the small blood vessels are not visible on a scan, but the brain damage in the form of microbleeds in the cerebrum or abnormalities in the white matter are. These are called 'white matter hyperintensities'. 'Lacunar (very small) infarctions and other subcortical infarctions (under the cerebral cortex) can also be visible. Furthermore, the spaces between the walls of blood vessels and the white matter of the brain can be visible; these are the 'perivascular spaces'. C-reactive protein (CRP) can be elevated in the blood. This is a non-specific indication of inflammation somewhere in the body. CRP is predictive of SVD and is elevated when the condition is really obvious.

Vascular risk management for prevention

In addition to monitoring and treating vascular risk factors, scientists recommend that a special outpatient clinic be set up for vascular disease.

Society needs to be better informed about the risks of vascular disease.

"A person with SVD now sees a neurologist for memory failure and other consequences of lacunar infarcts, an ophthalmologist for vision failure, a nephrologist for kidney failure, a cardiologist for heart failure, and a family physician and geriatrician/geriatrician for vascular risk factor monitoring, which should really be in one specialty," says Dr. Hakim of the University of Ottawa, Canada. Faculty of Brain and Mind Research Institute.

Read the current guidelines for the Dutch policy for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease: cardiovascular risk management.

Radboud University Nijmegen Research

According to researchers from Radboud University Nijmegen in their Diffusion Tensor and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Cohort (RUN DMC)

it appeared that there is both progress and decline in SVD over the years. It concerns the hyperdensity or hyperdensity; change and weakening of white matter, also called leukoaraiosis.

The white matter in the brain consists of the connections (axons) between the brain cells. The name comes from the white insulation layer (myelin) around these connections. In SVD there is demyelination and axonal loss.

It was shown that people with moderate or severe white matter hyperdensity (WMH) had a high chance of increasing their SVD, while participants with mild SVD showed a mild increase over a period of 9 years. In 3.6% of the study participants, the lacunae disappeared and in 5.7% of the participants, the microbleeds disappeared, but the white matter hyperdensities could increase.

According to these researchers, the progression of SVD is 'non-linear'. That is, it does not follow a certain 'straight line' of decline over the years.

The decline accelerates with increasing age. In addition, the SVD increase is a highly variable process.

Equally important, the researchers found that people with

mild white matter hyperdensity (WMH) rarely showed an increase over the nine years of the study.

See the images of the study od Radboud University Nijmegen

Resources

Hersenletsel-uitleg

Hakim AM. Small Vessel Disease. Front Neurol. 2019 Sep 24;10:1020. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01020. PMID: 31616367; PMCID: PMC6768982. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6768982/

Fazekas F, Kleinert R, Offenbacher H, Schmidt R, Kleinert G, Payer F, Radner H, Lechner H. Pathologic correlates of incidental MRI white matter signal hyperintensities. Neurology. 1993;43:1683–1689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Holland PR, Searcy JL, Salvadores N, Scullion G, Chen G, Lawson G, et al.. Gliovascular disruption and cognitive deficits in a mouse model with features of small vessel disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2015) 35:1005–14. 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.12 [PMC freearticle] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

Mitaki S, Nagai A, Oguro H, Yamaguchi S. C-reactive protein levels are associated with cerebral small vessel-related lesions. Acta Neurol Scand. (2016) 133:68–74. 10.1111/ane.12440 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

Poggesi A, Pasi M, Pescini F, Pantoni L, Inzitari D. Circulating biologic markers of endothelial dysfunction in cerebral small vessel disease: a review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2016) 36:72–94. 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.116 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [GoogleScholar] [Ref list]

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laneur/article/PIIS1474-4422(23)00293-4/fulltext

van Leijsen, Esther & Uden, Ingeborg & Ghafoorian, Mohsen & Bergkamp, Mayra & Lohner, Valerie & Kooijmans, Eline & Holst, Helena & Tuladhar, Anil & Norris, David & Dijk, Ewoud & Rutten-Jacobs, Loes & Platel,Bram & Klijn, Catharina & Leeuw, Frank-Erik. (2017). Nonlinear temporal dynamics of cerebral small vessel disease: The RUN DMC study. Neurology. 89. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004490.

Brain White Matter: A Substrate for Resilience and a Substance for Subcortical Small Vessel Disease

Walker KA, Power MC, Hoogeyeen RC, Folsom AR, Ballantyne CM, Knopman DS, et al.. Midlife systemic inflammation, late-life white matter integrity, and cerebral small vessel disease: the atherosclerosis risk incommunities study. Stroke. (2017) 48:3196–202. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018675 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol2013;12:822–838.

Wardlaw JM, Valdés Hernández MC, Muñoz-Maniega S. What are white matter hyperintensities made of? Relevance to vascular cognitive impairment. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015 Jun 23;4(6):001140. doi:10.1161/JAHA.114.001140. Erratum in: J Am Heart Assoc. 2016 Jan 13;5(1):e002006. PMID: 26104658; PMCID: PMC4599520.Prins ND, Scheltens P. White matter hyperintensities, cognitive impairment and dementia: an update. Nat Rev Neurol 2015;11:157–165.Banerjee G, Wilson D, Jager HR, Werring DJ. Novel imaging techniques in cerebral small vessel diseases and vascular cognitive impairment. Biochim Biophys Acta2016;1862:926–938

By National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health - http://training.seer.cancer.gov/anatomy/cardiovascular/blood/classification.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45154160 curid=45154160

www.scientificanimations.com, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4599520/